TSDI (Tourism Sustainable Development Index) is a sustainable tourism index developed by Murmuration and based on Earth observation space data and socio-economic data.

TSDI reflects the correlation between the economic development of tourism and its environmental impact. It is inspired by Professor Jason Hickel’s Sustainable Development Index (SDI), which aims to evolve the HDI (Human Development Index) to include environmental impact.

The added value of TSDI is the addition of a tourism dimension. In addition, the SDI assesses developments at a country level, while TSDI obtains a finer measure based on available data extracted from satellite remote sensing data.

The development of TSDI has led to the creation of a map on the Flockeo website (Flockeo is a platform which aims to develop sustainable tourism). This map provides travelers with scientific information on a country’s sustainability, helping them to choose a vacation destination that respects the 3 pillars of sustainable development.

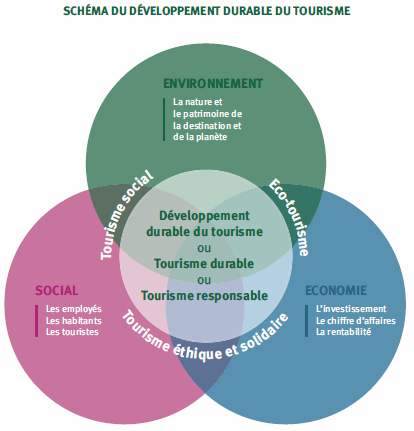

Sustainable tourism is defined by the World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) as “tourism that takes full account of its current and future economic, social and environmental impacts, addressing the needs of visitors, the industry, the environment and host communities“. It aims to achieve a balance between the three pillars of sustainable development in the production and implementation of tourism activities.

Sustainable tourism is also about the responsibility of individual travelers. They can take action by paying attention to their travel behavior (waste sorting, respect for protected areas, responsible water use, etc.) and their choice of tourism operators or destinations, according to sustainability criteria.

Figure 1 – The three pillars of sustainable tourism (Atout France)

TSDI is calculated by combining two components:

TSDI is mathematically a ratio between these two factors. Human and Tourism Development is the numerator. The higher it is, the higher TSDI. Environmental Risk is placed in the denominator. The higher it is, the lower TSDI. Each component is developed from sub-indicators. TSDI is rated on a scale of 1 to 10

This component is developed from the following sub-indicators:

Health is assessed by comparing the life expectancy of inhabitants with the highest and lowest life expectancy recorded among the countries of the world over the current period. The data comes from INSEE.

The level of education is assessed by comparing each country with the highest level of education in the world. It is based on the average between the number of years spent at school by the adult population (+ 25 years old, sexes combined) and life expectancy at school from kindergarten to higher education. Data supplied by Unesco.

Quality of life is measured by Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita. GDP per capita is assessed by comparing each country with the highest and lowest GDP in the world. The data comes from the International Monetary Fund.

This indicator provides information on the volume of tourist arrivals per year (international tourism). The total number of visitors is divided by the country’s population to obtain a number of tourists per inhabitant. Tourist attractriveness is assessed with a threshold of 2 tourists per inhabitant. Data from UNWTO.

This indicator shows the amount of tourism income generated in a country. A threshold is set at 10 billion dollars, beyond which countries that exceed it have the highest possible score and are not further valued. Data supplied by UNWTO.

This component is developed from the following sub-indicators:

Air quality is assessed over the year (previous year of current year). The satellite data used come from CAMS, Global atmospheric composition.

Six contaminants are assessed according to WHO criteria:

WHO criteria set daily limits not to be exceeded in ?g/m3. The effective concentrations of contaminants in the area are averaged over the day and compared with these limits. If all average concentrations respect these limits, then the day studied is counted as a respected day over the period studied. This process is repeated for each day of the study period to establish a score on a scale of 0 to 10. If 90% of the time during the studied period, the contaminants emitted are below the limits, then the risk is considered zero for TSDI. Thanks to satellite data, all countries are evaluated on this indicator.

The Water Resources score is based on an aggregate indicator derived from the work of the World Research Institute (Aqueduct platform). It includes a dozen indicators, such as water stress and flood risk. This risk is converted into a score for TSDI. The total is then converted into a score from 0 to 10. 127 countries are evaluated on this indicator.

This sub-indicator indicates the preservation of forest cover over the last 20 years. A country that has preserved or increased its forest cover over this period will be rated highly. On the other hand, a country that has deforested will receive a low score. The data source is the Modis satellite indicator ” “MOD44B.006 Terra Vegetation Continuous Fields Yearly Global 250m”.

The evolution of the forest between 2003 and 2010 is compared with the evolution between 2011 and 2020. To achieve zero risk, the area’s forest must be preserved. If the forest trend is negative, deforestation is taking place and the environmental risk is increasing. Thanks to satellite data, all countries are assessed on this indicator.

A fourth indicator has been added to compare carbon emissions linked to national consumption (Global Carbon Atlas) with the government directives put in place as part of the Paris Agreement1 (Nationally Determined Contributions).

56 countries2 are evaluated on this sub-indicator. Global Carbon Atlas data estimates carbon emissions generated by a country’s consumption (local production and imports), which is different from territorial emissions (local production and exports). NDCs are studied in the context of net emissions reduction. The difference between these two data provides a score, always evaluated from 0 to 10. A maximum deviation of 12.5% between decisions and actual emissions is tolerated within TSDI.

Countries are eligible for TSDI if they provide UNWTO with up-to-date data on their tourism activity. This is the guarantee that the country has a tourism activity.

A country is eligible for TSDI if it provides sufficient data to calculate the sub-indicators. The absence of data can lead to biased results. At least two indicators are required for each TSDI component. Furthermore, if the education and life expectancy indicators are missing, then the representation of the population is zero and therefore TSDI score is penalized.

In this ranking, the latest available data are used for each indicator.

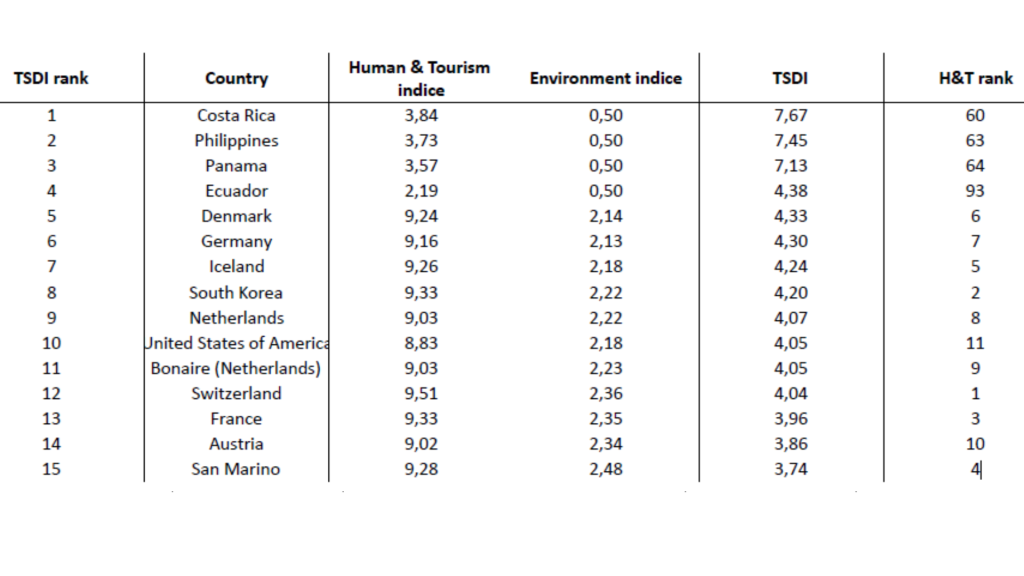

TSDI Ranking – ©Murmuration

The full results table is available for download here. For further details, please contact us at contact@murmuration-sas.com.

TSDI highlights the right balance between human and environmental development. Tourism and/or human pressure have an impact on the environmental score and therefore on TSDI.

The higher the environmental risk, the worse TSDI. The environmental risk can divide TSDI by up to 4. On the contrary, if the environmental risk is low, TSDI will be less impacted, or even valorized. This can be multiplied by two if no environmental risk is detected.

Examples: Costa Rica, the top-ranked country, presents little or no Environmental Risk. It is therefore valued and scores 7/10. To obtain 10/10, Costa Rica could increase its attractiveness to tourists, which would raise its Human Development and Tourism score.

Canada ranks 56th out of 155 in TSDI rankings. This country has been penalized in Human and Tourism Development because of a tourism affluence in 2021 close to 1/10. We can presume that the Covid-19 crisis is partly responsible for these figures. The highest Environmental Risk for this country is in Air Quality, where Canada scores 2.1/10. Ozone is responsible for this low score. This gas is produced in hot weather. It is also produced by vegetation cover (35% of Canada is covered by forests). Ozone formation is thus dependent on meteorological conditions (high solar radiation, high temperatures) and the country’s geography. Canada is therefore penalized in TSDI by ozone, which represents a risk to human health in the event of excessively high concentrations in the air.

TSDI is a sustainable tourism index that evaluates countries according to a scientific method. The sub-indicators are transparent and guarantee a reliable Environmental Risk analysis, while taking into account essential Human Development indicators. TSDI results map is available on the Flockeo website

For further details, please contact us at contact@murmuration-sas.com.

TSDI Map: Flockeo

ATD: Acteurs du Tourisme Durable

Air Quality: CAMS global atmospheric composition forecasts

Water Ressource: Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas

Forest cover: MODIS de Google Earth Engine

CO2 emissions compared with the Paris Agreement’s Nationally Determined Contributions: Global Carbon Atlas, NDC database

Life expectancy: Insee

Education: UNESCO

Gross Domestic Product: IMF

Tourism attractiveness and income: OMT

1The Paris Agreement (2015) is a legally binding international treaty on climate change. Signatory states pledge to hold “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels” and pursue efforts “to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.”, https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement

2The 56 countries evaluated are those aiming to reduce their emissions by 2030.

Sri Lanka, this island state located in the south-east of India, contains an incredible biodiversity due to the diversity of the natural environments it shelters, such as the Sinharaja Reserve. Its specific geographical location on a geological fault and its humid tropical climate make it an ideal environment for numerous endemic species such as the Sri Lankan elephant, which live in the midst of lush green flora.

Relative to its small size, the island has a remarkable diversity of forests with one of the highest biodiversity concentration indices in the world (2.17 BioD index). These are distributed as follows: 70% dry tropical monsoon forest cover, 15% tropical rainforest and 5% low relief tropical montane forest. Covering more than 15,500 km 2 , the forests are distributed through local policies through several dozen protected nature reserves. These generate significant flows of tourism representing nearly 10% of the country’s GDP. The attraction of the encounter with sacred places, the population and this local biodiversity has indeed generated, in a pandemic context in 2020, the arrival of 540,000 tourists.

Affected by this massive influx of tourists, the country has in recent years embraced the transition to more ethical and sustainable tourism. This has led many key players in the industry to rethink their approach to travel. Initiatives such as the Eductours now offer both Sri Lankan professionals and international agencies the opportunity to discover concrete positive initiatives and to amplify synergies towards the tourism of tomorrow.

On the occasion of the Eductour organised by Flockeo with 4 agencies in Sri Lanka within its network during the first week of May 2022, we wanted to re-examine the situation of protected areas in Sri Lanka through the prism of the tourism issue. To do so, we once again used satellite data analysis to understand the anthropogenic impacts on ecosystems.

We then focused on the Sinharaja Reserve, located in the southwest of Sri Lanka. We studied the evolution of its biodiversity and analysed the importance of the existence of such a protected natural reserve through the carbon sequestration of this forest.

Sri Lanka has a unique flora and fauna, which benefits from an island with vast, unspoilt natural areas.

Sri Lanka’s forests are made up of 60% of the island’s endemic trees, with a further 50% of endemic mammals. There are also unique butterflies, insects, reptiles and amphibians that are found only in Sri Lanka.

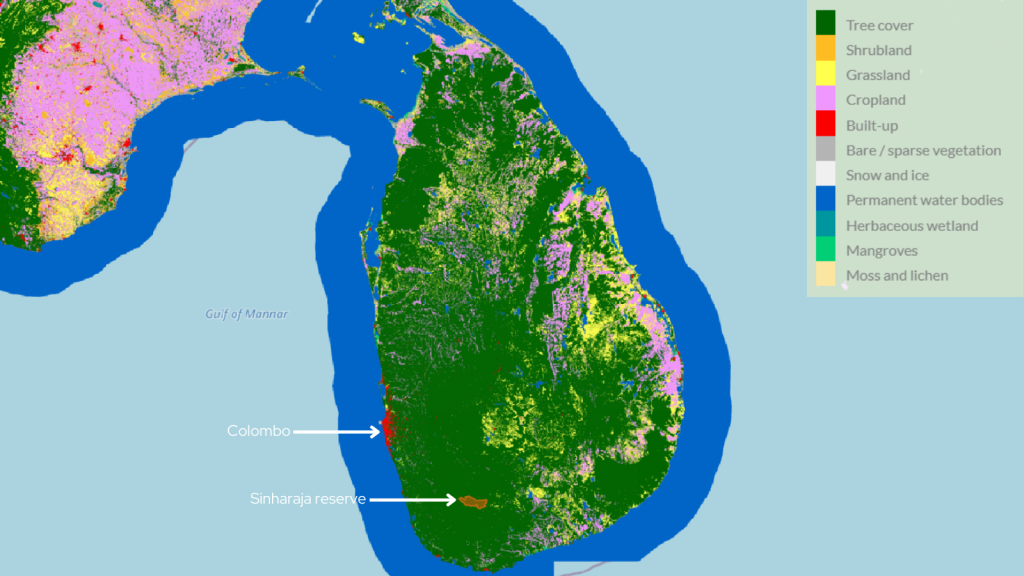

The importance of natural areas and biodiversity in Sri Lanka is very high. These areas still cover a major part of the island. This is even more striking when the island is viewed from space using satellite data.

Using the land use indicator, the forest and green dimension of the island is fully apparent.

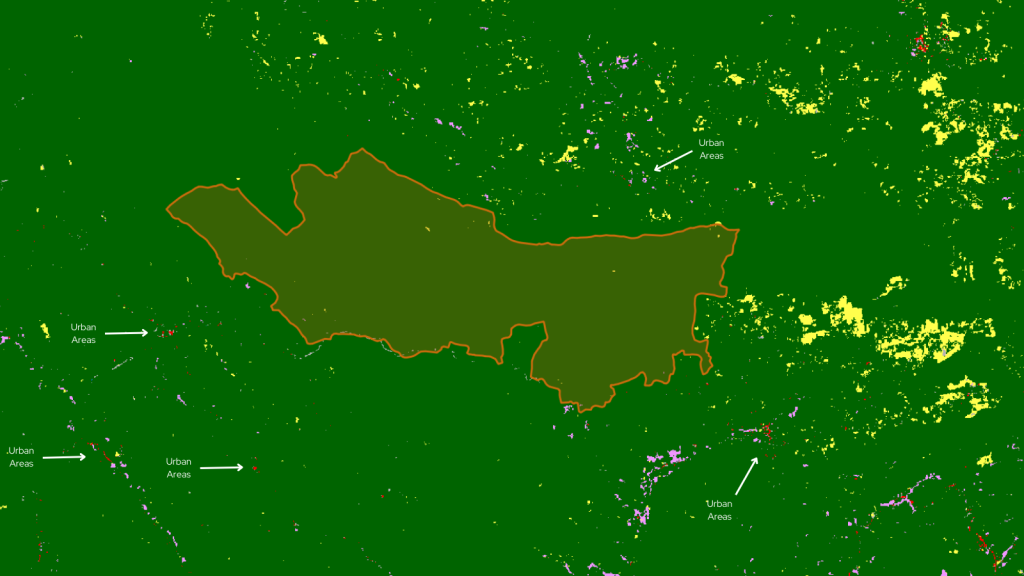

(Land Cover Indicator Map of Sri Lanka, 2020, ©Murmuration)

First of all, we can see that most of the island is covered by trees (in green). It can also be seen that arable land covers a significant part of the eastern part of the country. Finally, the land use indicator highlights the presence of urban areas (in red), the most important being Colombo in the west of the country.

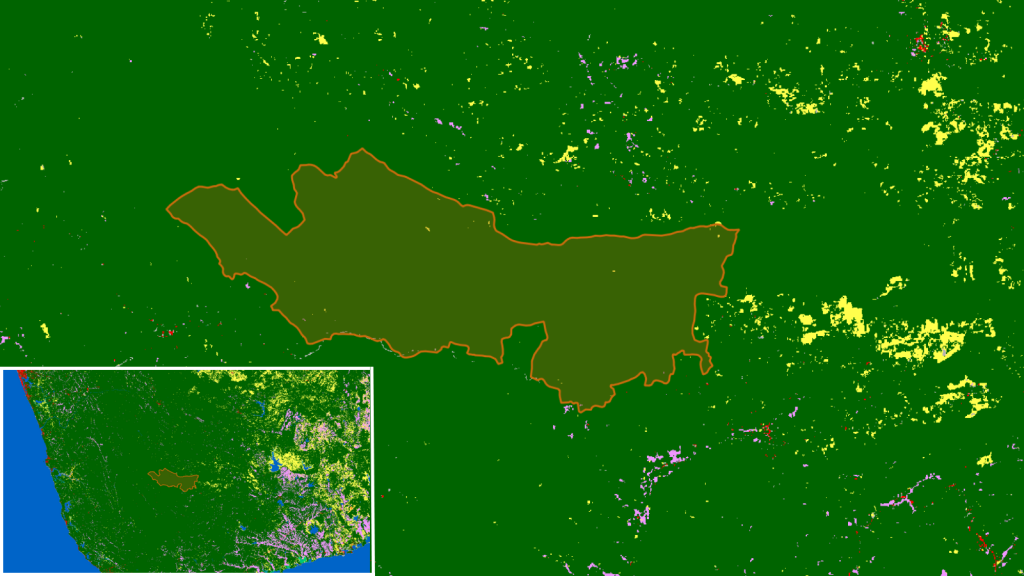

The Sinharaja Reserve has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1989. It is considered the last viable area of primary rainforest in Sri Lanka. It covers more than 8,000 hectares, in the heart of an already heavily forested region.

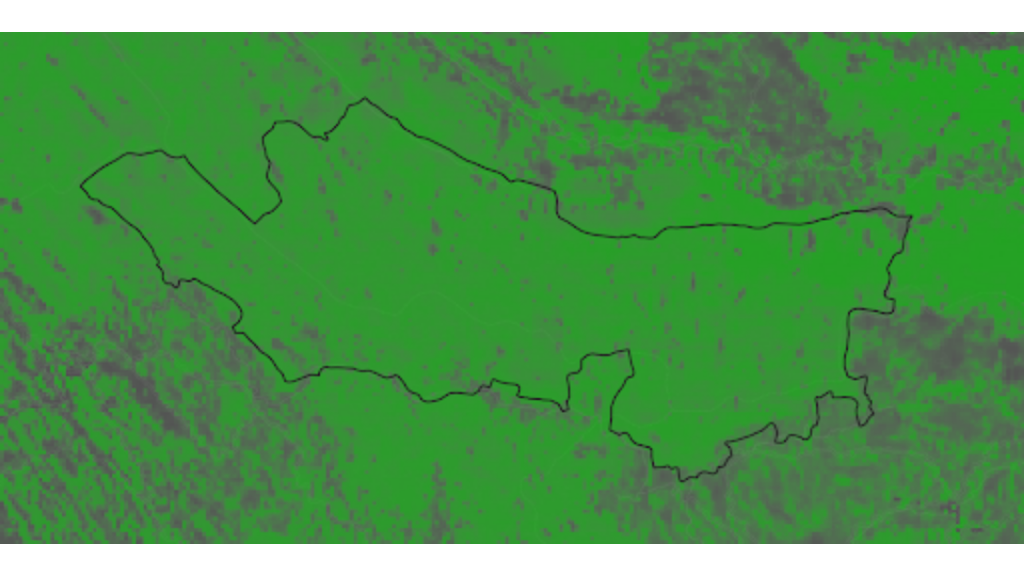

(Land Cover Indicator of the Reserve of Sinharaja, Sri Lanka, 2020, ©Murmuration)

This forest is very little altered (exclusively green area), which proves the necessity of protecting these green areas and the positive results of this protection. It is clearly visible from space that this area is almost untouched by urban construction or agricultural cultivation.

This is due in part to the status of this biodiversity area as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. It also benefits from real protection by the Sri Lankan public services. Finally, it also benefits historically from the lack of road access to the reserve.

We are therefore in the presence of an authentic primary forest, i.e. a forest composed of indigenous species where no trace of past or present human activity is clearly visible.

(Vegetal Cover Indicator Map of the Reserve of Sinharaja, Sri Lanka, 2020, ©Murmuration)

Focusing on the vegetation cover of the area, the Sinharaja Reserve (center, in darker red) can be clearly seen. The darker is the red, the more vegetation is present on the land.

However, as highlighted in this article, establishing the health and sustainability of a forest is not usually based solely on its vegetation density.

To monitor the biodiversity of the Sinharaja reserve, we used our vegetation health indicator, obtained by calculating the NDVI (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index). Based on spatial Earth observation data, it allows us to assess the content and evolution of vegetation in a territory.

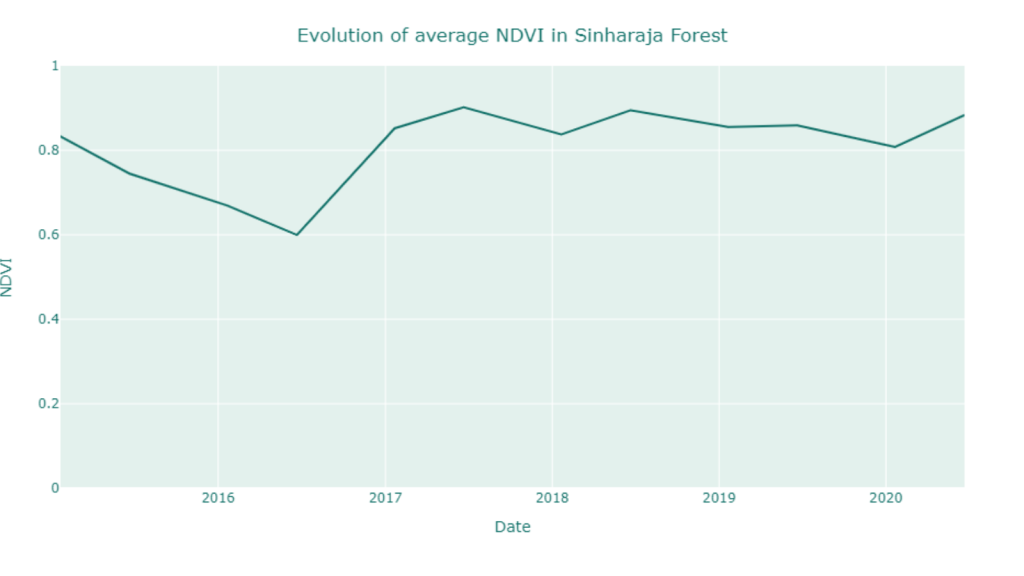

(Evolution of the Average NDVI in Sinharaja Reserve, 2 samples a year, 2015-2020, ©Murmuration)

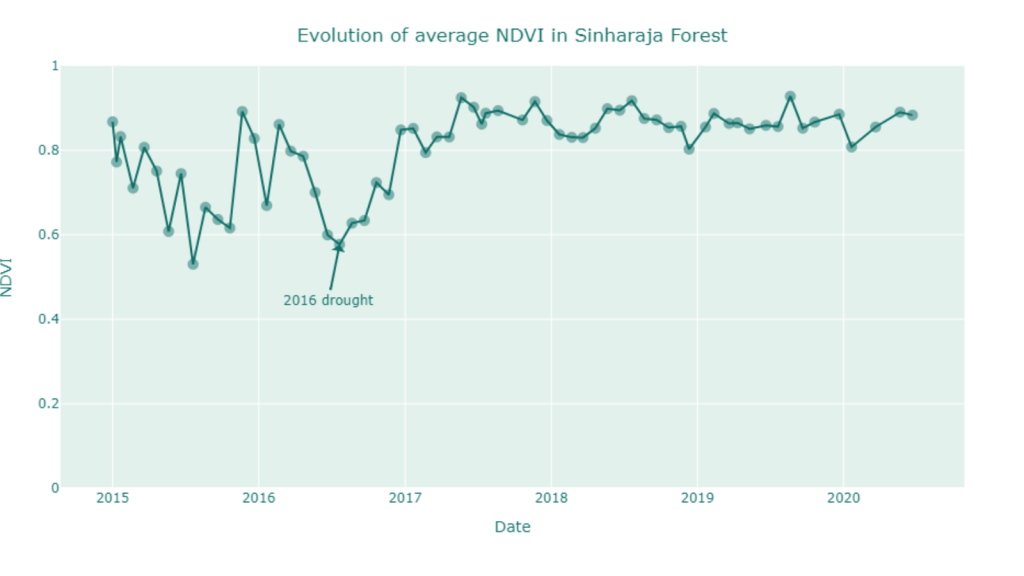

(Evolution of the Average NDVI in Sinharaja Reserve, 1 sample every month, 2015-2020, ©Murmuration)

The graphs above show the evolution of the average health of the vegetation from 2015 to 2020.

Two phenomena should be highlighted:

The use of this vegetation health indicator allows the state of the green spaces to be quantified precisely and comprehensively. However, it is important to emphasise that indicators here are 6-month and 1-month average of a natural phenomenon that is constantly changing. In addition, there are many climatic, environmental and anthropogenic phenomena that influence the health of the vegetation.

In Sri Lanka, biodiversity is notably subject to two monsoon seasons: Yala and Maha. Yala takes place in the southwestern part of the island from May to July. This is the great monsoon, creating a very humid climate.

Maha, is the second monsoon period, on the North East coast of Sri Lanka. It usually occurs from October to January.

These two periods play an essential role in the development and preservation of Sri Lanka’s biodiversity.

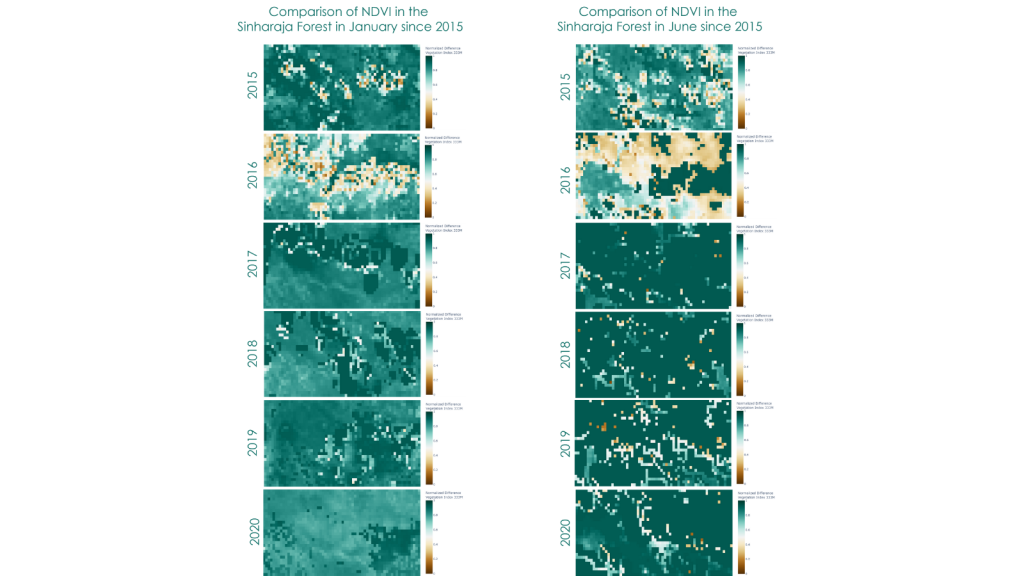

(NDVI Map of Sri Lanka, 2015- 2020, ©Murmuration)

This systematic evolution of biodiversity is visible from space, by observing the vegetation health indicator during the different seasons and over several years (2015-2020).

Real variations can be seen: biodiversity evolves, moves, clusters and expands with each monsoon.

Therefore, climate change plays an important role in the evolution of Sri Lanka’s biodiversity. The lack of monsoons, or the reduction of rainy days are real factors that threaten Sri Lanka’s biodiversity.

Biodiversity must be protected at all costs, as its role is crucial in the fight against carbon and climate change.

We have previously highlighted the fact that the Sinharaja reserve is a primary rainforest. This is of particular importance for understanding the role of biodiversity in the fight against climate change.

Our carbon sequestration indicator allows us to highlight the role that a primary forest such as Sinharaja plays in this phenomenon.

(Carbon Sequestration Indicator Map of Sinharaja Reserve, 2020, ©Murmuration)

This indicator makes it possible to determine the quantity of carbon sequestered by the reserve, in this case 1 million tonnes of CO2 sequestered per hectare. The reserve is clearly visible in this image.

The green colour represents the areas sequestering carbon, the more intense the colour, the greater the quantity of carbon sequestered. In contrast, grey represents areas where little carbon is sequestered.

To put it another way, the forest of the Sinharaja reserve alone retains nearly 9 billion tonnes of carbon. By comparison, the annual carbon output of global aviation is approximately 660 million tonnes of CO2/year.

If this figure seems so high, it is essentially due to the age and preservation of this area of biodiversity. Virtually untouched by human disturbance, the forest has been able to accumulate a gigantic amount of carbon from its birth to the present day.

The forest absorbs carbon from the air and transforms it into branches, leaves and all forms of vegetation. In doing so, the forest absorbs CO2, retains the carbon for its development and releases O2 into the air. This phenomenon, called photosynthesis, is the source of carbon capture by forests.

It is therefore important to emphasise that the Sinharaja reserve does not consume nearly 9 billion tonnes of carbon per year, no, it is made up of carbon!

This forest has absorbed all this carbon since the beginning of its existence (which can represent several thousands or even millions of years), but it does not disappear, it is present in the wood of the trees.

In the course of these analyses of biodiversity in Sri Lanka, and in particular vegetation, several threats to the Sri Lankan environment are observed.

Firstly, the ultimate need to protect the Sinharaja reserve, in order to avoid any release of carbon into the atmosphere. This is already very difficult to control today, and any further release is a step backwards in the fight against climate change.

The territorial protection of the reserve is of great importance as it is subject to many pressures, be they urban, economic and/or social.

(Land Cover Indicator Map around the Sinharaja Reserve, Sri Lanka, 2020, ©Murmuration)

The reserve is confronted with urban pressure and the phenomenon known as “urban sprawl”. Indeed, towns are taking up more and more land and people are settling ever closer to natural areas. As can be seen in this map, some small towns are not far from the reserve and are already taking land from the forest around them.

In order to meet human needs for access to work and health care, Sri Lanka has built new roads, which are coming dangerously close to the Sinharaja reserve, and in some cases already threaten the reserve.

These roads are being built to give residents easier access to services that are only available in the larger towns.

Although the construction of this road is motivated by important human needs/necessities, it is important to measure its immediate impact on nature, but also those to come, which are also called negative externalities.

Indeed, the construction of a road will not only have environmental consequences of the construction, but also of the use of the road. We are talking here about the traffic to which these roads will be subjected, and therefore the penetration of polluting vehicles as close as possible to the nature reserve.

Finally, these roads can also be diverted from their basic principle and used for profoundly anti-environmental economic purposes. The opening of such roads increases the number of access points to the forest and thus facilitates access to illegal exploitation of the forest and illegal resource extraction.

To combat these negative externalities, several solutions can be envisaged.

Firstly, constant monitoring of the forest (in particular through the use of satellites). Secondly, increased funding for the protection of the integrity of the forest, including the addition of staff to monitor and punish infractions.

The financial contribution of tourism, attracted by this reserve, can and should be a source of funding for the protection of Sri Lanka’s biodiversity.

(Comparison of NDVI in the Sinharaja Reserve , in January and June, 2015-2020, ©Murmuration)

As can be seen from these images, the vegetation cover came to a considerable halt in 2016.

This year was known to be one of the driest on record. The major consequence of this drought, which can be seen regardless of the season, was the regression of the vegetation space in the reserve.

This phenomenon has been observed in several places around the world. It shows the extreme vulnerability of plant areas to climate change.

This environmental phenomenon raises a series of questions concerning the struggle of state and social actors against international and climatic phenomena.

In addition, such events underline the importance of the need for a global effort to combat global warming, which directly threatens the world’s biodiversity, our forests, our oceans, and consequently the air we breathe.

The protection of the biodiversity is now more than ever a major concern of human’s health and future.

Sources : Copernicus Programm

Authors : Maël Plantec, Camille Lainé, Muruguesh Manthiramoorthi, Fabien Castel, Rémi Nassiri

Murmuration is pleased to announce its selection as the French organizer of the 3rd Cassini Hackathon, a European Union programme.

To achieve this, we have partnered with Open Tourisme Lab based in Nîmes, who bring their expertise in supporting entrepreneurs and start-ups.

This 3rd edition of the Hackathon will be on the theme of (Re)Vitalizing Tourism in Europe. It will highlight the use of technologies and spatial tools to innovate and revitalize the tourism industry in Europe in a responsible way.

To achieve this, 3 challenges have been identified: Finding sustainable destinations; Experiencing cities and cultures; Caring for our wildlife.

These challenges are aimed at students, entrepreneurs, or anyone with the desire to innovate and act sustainably.

It is therefore with pleasure that we announce that the CASSINI Hackathon will take place from 12 to 14 May 2020 in Nîmes.

Big cities keep on growing, it is important to monitor this development process, and that’s why Murmuration created its own Urbanisation Indicator. As a result of technological progress, humanity is constantly expanding its urban territory. This phenomenon of urbanization leads to an artificialization of the soil and poses three major problems:

Nowadays, three solutions exist to answer these problems :

Murmuration proposes an Urbanization indicator, built from satellite data. Today, a city or a village is quite capable of determining the evolution of its urbanization without using spatial data. However, it is at a more global scale that the task becomes more complex. Indeed, for a region or a country to be able to calculate the evolution of its urbanization, it would be necessary for all the sub-communities to gather their data together.

The Urbanization indicator is an observation tool that allows the visualization of land artificialisation in a given area of the world at a given time. It also allows to study its evolution between two years. To better understand how it works, here are two images.

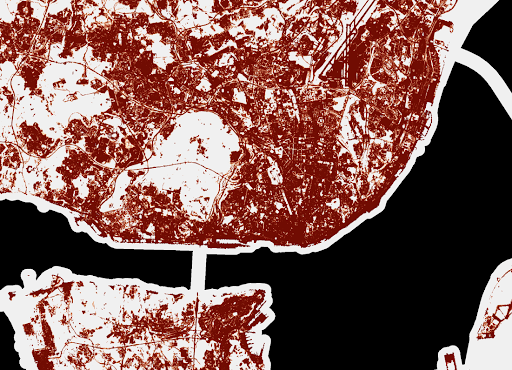

(Urbanism map of Lisbon, 2018, ©Murmuration)

This is an image representing the density of land taking process in Lisbon in 2018.The accuracy is 10 meters. The density is calculated as a percentage. The darker the area is red, the higher the density of land taking process. Conversely, the lower the density of an area, the more it will be represented in light red, until it becomes white if the area is not artificialized.

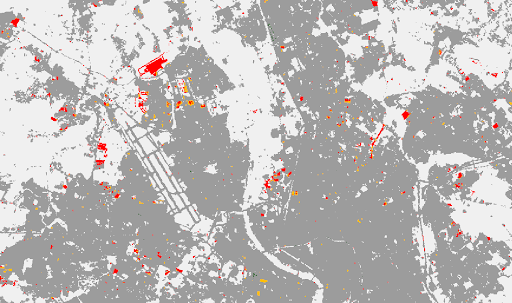

(Evolution of land artificialisation in Toulouse between 2015 and 2018, ©Murmuration)

Finally, this image represents the evolution of land artificialisation of a part of the city of Toulouse between 2015 and 2018. The accuracy is 20 meters. the areas in dark gray t have not evolved between the two periods. In red and yellow, are the areas where we built. In green, these are the areas where the artificialization has decreased (creation of park, destruction of building, …). Finally, in white, these are the undeveloped areas.

To operate, the indicator uses three different databases. The first is from the Wekeo service. This company offers Copernicus data for free download, including all Sentinel satellite data, contributing missions and Copernicus marine, terrestrial, atmospheric and climate services. We can find the data of soil impermeability in Europe with a precision varying between 10 and 100 meters depending on the selected options. These data are present every 3 years, from 2006 to 2018 and are accompanied by data showing their evolution over the same period.

However, this service only offers soil impermeability data in Europe. This is why we use a second database from the Copernicus Global Land Service. This organization offers data displaying the built-up areas in the world, from 2015 to 2019, with a precision of 100 meters. We can then calculate ourselves the evolution of these areas between each year.

Finally, for the most recent years and for a worldwide observation, the database from the World Cover service is used. WorldCover provides a new reference product for global land cover at 10m resolution for 2020, based on Sentinel-1 and 2 data that have been developed and validated in near real time and at the same time maximize the impact and usability for end users.

To better understand the usefulness of such an indicator, let’s see how we can study the evolution of urbanization in Occitania in relation to the objective “Net Zero Artificialization” (NZA).

This objective in France aims at limiting the increase of the impermeability of the soils in order to reach a zero growth in 2050. Thanks to the urbanization indicator, we can see that the Occitanie region has experienced a growth of 3.4% between 2015 and 2018.

Even though such growth seems to show that the ZAN goal is not met, it should be understood that the region is one of the most attractive in the metropolis, with a population growth of 3.5% between 2013 and 2018 according to INSEE.

In order to evaluate the achievements of the Net Zero Artificialisation’s objectives, Urbanisation Indicator seems to be the most adequate. It allows a larger time and space analysis.

On the other hand, it can be seen that urban growth is difficult to compensate. When a natural area is artificialized, there is little chance that it will return to its original state.

Indeed, between 2012 and 2018 only 0.01% of the artificialized territory in Occitania has undergone a significant decrease in its imperviousness.

Finally, it is interesting to study the impact of major cities on the increase in net land artificialisation in Occitania between 2015 and 2018. Toulouse, which is the region’s capital, alone absorbs 8.2% of all urban growth while constituting only 4.87% of the urban area in Occitanie.

Montpellier, which is the second largest city in the region, absorbs 3.2% of all urban growth, while it only constitutes 2% of the urban area in the region. One might therefore think that the metropolises act as catalysts for soil artificialisation.

However, these are the same cities that have the highest density in the region and therefore limit urban expansion to a maximum. The large cities therefore have a double-edged impact on land artificialisation.

Thus, it is important that the city councils of these metropolises continue to develop their urbanization while applying the three methods for limiting the net artificialisation of land: avoid, limit and compensate.

Tomorrow, millions of people around the world will leave their jobs or homes to join the global climate strike on the streets and demand the end of the fossil fuel era.